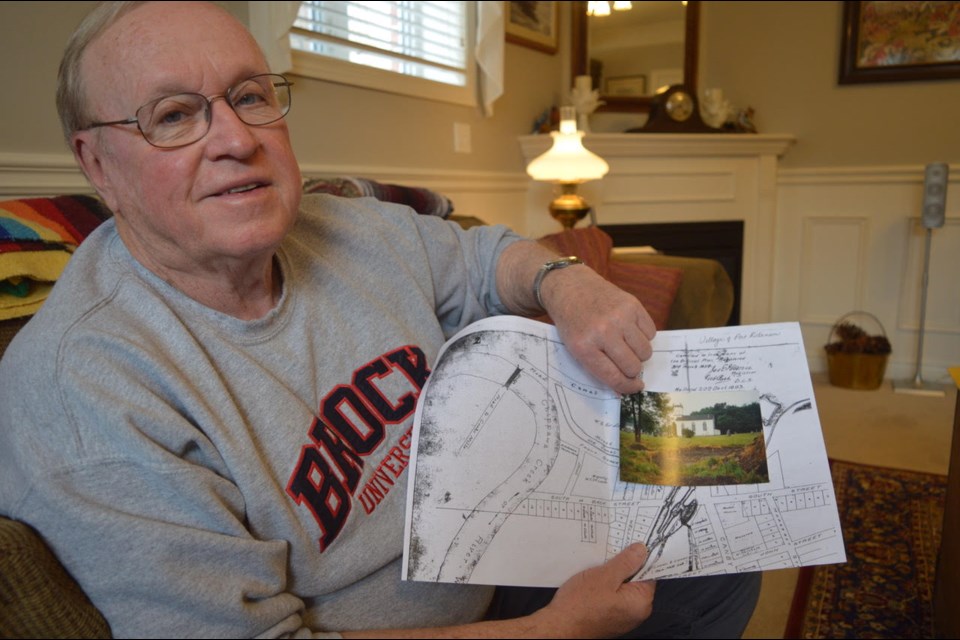

With a house filled with memorabilia and artifacts that speak to previous eras, Tom Russell, member of the Thorold Museum and vice-chair of Local Architectural Conservancy Advisory Committee, LACAC, as well as other local historians realize the role blacks played in building and protecting the Niagara area, and more specifically Thorold and Port Robinson.

Dating back to the early 1800’s, those that morally opposed the slave trade in the U.S. developed a clandestine route to bring slaves into Canada, known as the underground railroad. In May of 1844, St. Paul’s Anglican Church in Port Robinson opened, and was the only known church in the area that would provide religious services to blacks, said Russell, who has devoutly researched Thorold’s roots. During that time, construction of the second canal and its locks were underway, and many villages like Thorold and Port Robinson sprung-up and prospered around them.

More importantly, the construction of the canals attracted many Irish immigrants, who fought over their Protestant or Roman Catholic religious convictions and differences. During that time, the 43rd infantry of the British regiment was created, which was comprised of blacks, for the sole purpose of maintaining the peace, which was not always an easy task. On the weekends, there were brawls in the local pubs, mainly between the Protestants and Catholics, and the infantry had to prevent uprisings and maintain order, noted Russell.

Russell’s historical documents state: The violence came to a head in 1849 when Irish workers marched to Port Robinson where the troops were stationed in protest of the 43rd infantry, known as “the coloured corps”. Many villagers had also been sworn in as special police to stop this upheaval.

An excerpt from his documents state: “Disaster was averted when an Irish Catholic priest from St. Catharines, Father McDonagh rode up on horseback and threatened to ban them from the church and was striking out with his riding crop.”

In retrospect, expressing the Irish sentiment, Russell said: “Imagine seeing a black man in a red uniform telling white men what to do,” he said adding: “the red uniform represented the British crown, and you have to think of the times.” On one hand, Russell concedes, the British army attracted many runaways, because they were free, and they were given “food, clothing and a job,” he said. In contrast to the U.S., living in Port Robinson: “had to be an incredible experience for them.”

On the other hand, the existing laws and co-habitation of immigrants from different belief systems created many racial and religious tensions.

Russell admits while slavery might not have been popular in Niagara, not everyone accepted the equality of blacks under the law yet. “Many white officers would not stay with black soldiers,” so tents were set-up on the property adjacent to the Anglican church where they lived from about March to November when construction on the canal was being done. At the Anglican church, blacks attended service every Sunday, but they were segregated, although that term was not used at the time, explained Russell. Many of the blacks were seated in the upper tier/balcony of the church, he said. However, that infantry donated a significant amount of money each month to help pay off the mortgage of the church.

While many Canadians believe there were no slave owners in Canada, Russell said that’s quite the contrary. Prior to the abolishment of slavery in 1833 here, “It’s public knowledge” and “documented” that around 1805, there were several families in Niagara-on-the-Lake who owned slaves. “How they treated them depended on the whim of the employer,” but they were mainly treated as “property,” just like furniture or livestock, he said adding: “It’s terrible.”

Many bounty hunters also crossed the border into Canada searching for runaway slaves and would capture and return them to their “rightful owners in the U.S.”. “The bounty hunters made good money,” pointed out Russell.

In 1851, Russell notes James Bruce Elgin, the Governor General of Canada made an official visit to Port Robinson to inspect the completion of the second Welland Canal. He requested the 43rd infantry escort him around Niagara, much to the resentment of those harboring anti-black sentiment.

Fast forward to present day, twenty years ago, Russell said the Anglican church was selling its property, and needed to hire two archeologists from the diocese to ensure there were no human remains on the site.

He said animal, but no human bones were found, in addition to several artifacts, such as a pipe and several buttons from infantry uniforms, dating back to that period. Many of the records from all the Anglican churches in that era were transferred to McMaster University, but Russell being a collector and history buff requested to keep several mementos from the archeological dig. Monetarily, they’re not “worth anything,” but they remain priceless to him. “I’ve always loved history,” he added.

St. Paul’s Anglican Church closed its doors about eight years ago. Prior to its closing, Russell recalled a heart-warming experience which was to provide a Pennsylvanian woman, who was tracing her ancestry, an original document of her previous relative who was baptised in that church.

Russell also brought her to there, because she knew her great, great grandfather, “eight times removed,” was in the 43 rd infantry. When he took her to the church tower and her hands passed over the church railing where he’d been, she could feel his presence and she started to

cry.

“It’s the concept of the hands that touched the hand,” he said.