At the time of the Canal sod-turning ceremony in November, 1824, already contractors had been engaged for the work, and hundreds of immigrants, chiefly from Ireland, now came to find employment as labourers. The diggers received only 63 cents a day.

It is interesting to note that the original projectors of the scheme did not in their wildest hopes look forward to so stupendous an achievement as the new canal. The first idea was to connect the two lakes by means of a boat canal through the valley of the Twelve Mile Creek to the foot of the mountain ridge, while the incline was to be ascended by means of a railway ending at Beaverdams; from this point a second canal was to be tunneled through the hill that has since been excavated, and is now known as the Deep Cut.

Boats were to enter the tunnel from the Chippawa, a little east of the village of Port Robinson. Two shafts were sunk, and while the work went on, two flat boats to be used on this strange route were built. They were known by number, being 1 and 2 of the Erie and Ontario Navigation Company.

However, while the workmen were digging down to the level of the tunnel, they came upon a spring of water so great in volume that it swept off one of their number. Leaving their tools at the bottom, the others escaped as quickly as possible, and ran to the little settlement, reporting that a stream of water as large as a barrel had burst out upon them.

At any rate, the stream or spring was important enough to make the company abandon all thoughts of being able to construct an underground canal.

The second plan was also to bring the water from the Chippawa Creek, but it was now proposed to dig a channel through the troublesome hill that was to have been tunneled. The work was then all done with pick and shovel, and soon the men found a new difficulty in the quicksands. Slips of so disastrous a nature occurred that the company gave up the plan of bringing the water from the Chippawa, and decided to connect the canal with the Grand River, which is on a much higher level.

They were better able to do this, as in February, 1827, the Legislature of Upper Canada had taken stock to the amount of 50,000 pounds, and had also made a grant to the company of 13,000 acres of land in the township of Wainfleet, while the Government of Lower Canada had invested 25,000 pounds in the project. Just when the quicksands interfered with the work, it was estimated that the construction was so far advanced that in 10 days, the waters of the Chippawa could have flowed through the Deep Cut.

Experienced engineers were employed to survey a route from Caledonia to Port Robinson. They pronounced it perfectly practicable to bring the water from the Grand River, but estimated the cost at 25,000 pound more than the company then had on hand.

Nevertheless, as the canal between Lake Erie and the Chippawa was already completed, the directors determined to undertake the work in a new direction.

At the present town of Welland, an aqueduct was built over the Chippawa River, while a dam was constructed across the Grand River at Dunnville, and by means of an artificial channel called the Feeder, the pent-up waters of the latter stream were thus brought to the Deep Cut.

The great volume of water kept the banks in their places, and it was now possible to dredge out the bottom where the quicksands had refused to yield to pick and shovel. The canal was thus connected with the Chippawa River, and in this way two outlets were given to it—one through the Chippawa into the Niagara River, not far from its source, and thence into Lake Erie at, Buffalo; and the other through the Feeder and the Grand River to the same lake at Dunnville.

With this connection, it was easy to lock boats down from the level of the canal to that of the Chippawa Creek, and thus, a great difficulty was surmounted, for it would have been impossible to dig low enough through the quicksands to be able to feed the canal from the creek.

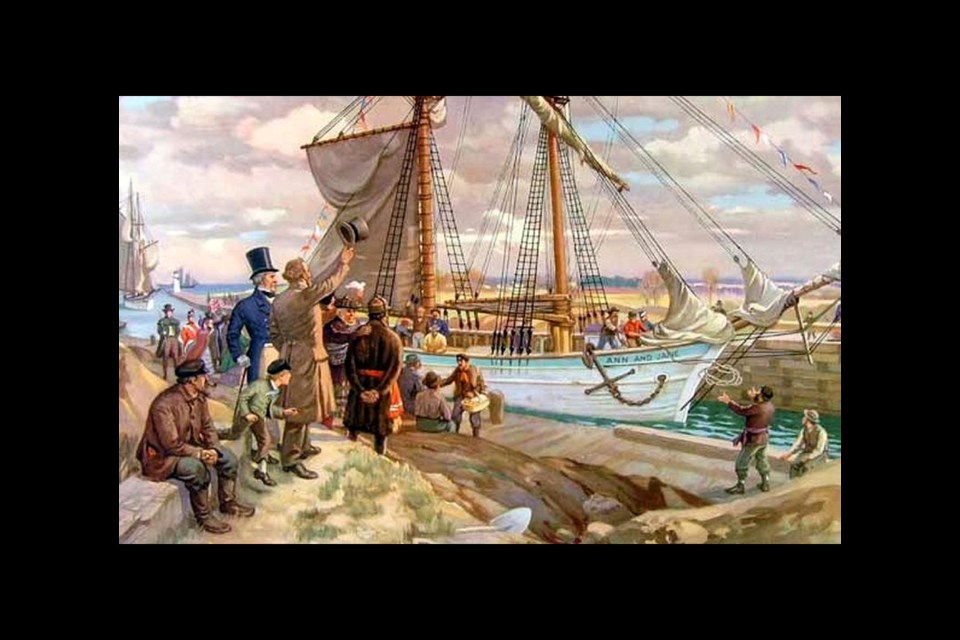

On the 30th of November, 1829, the first two vessels, the Ann and Jane of Toronto, and the R. H. Boughton of Youngstown, NY, passed up the canal from Port Dalhousie. All along the way, people turned out to witness this great event, which was celebrated with due honour. After some discussion on the question of precedence, it was decided that the British vessel should lead. The canal labourers themselves took turns in towing the boats, which were covered with flags. At Port Robinson, these vessels were let in through the guard locks to the Chippawa River, and then passed on to Lake Erie, thus formally opening the canal.